Notes on "Science and Statistics" by George Box, 1976

The following are my notes and outline of a paper by George Box on the role of statistics in science.

| Title | Science and Statistics |

| Author(s) | George E. P. Box |

| Source | Journal of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 71, No. 356 (Dec., 1976), pp. 791-799 |

| Publisher | American Statistical Association Stable |

| URL | http://www.jstor.org/stable/2286841 |

1 Introduction

Fisher was not just a great statistician, but a great scientist.

2 Aspects of Scientific Method

2.1 Iteration Between Theory and Practice

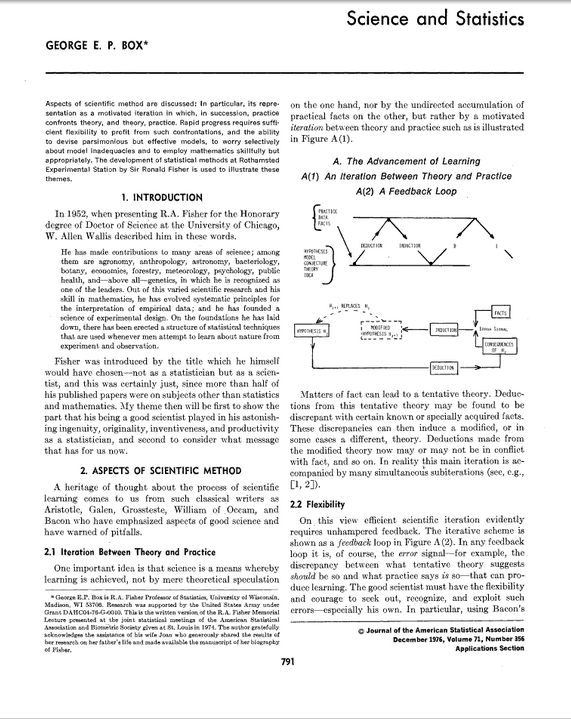

Learning is achieved by an iteration between theory and practice. Facts lead to the formation of a theory. The theory is used to predict outcomes. Discrepancy between prediction and experimentally known facts lead to a modified theory. The process repeats.

2.2 Flexibility

The iteration between theory and practice produces an “error signal,” the difference between what the theory predicts and what is known to be true. This is the feedback loop, and it what produces learning. Do not fall in love with the model; seek out error signals.

2.3 Parsimony

Seek to create simple models. Over-elaboration can be the mark of mediocrity.

2.4 Worrying Selectively

Since all models are wrong the scientist must be alert to what is importantly wrong. It is inappropriate to be concerned about mice when there are tigers abroad.

2.5 Role of Mathematics in Science

[We] cannot know that any statistical technique we develop is useful unless we use it. Major advances in science and in the science of statistics in particular, usually occur, therefore, as the result of the theory-practice iteration.

The statistician must practice in the field and set himself up to be directly involved in real-life theory-practice iterations.

Image source: http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/2286841

3 Fisher--A Scientist

This part explains how Fisher is a scientist, using for illustration his accomplishments at Rothamsted Experimental Station.

3.1 Rothamsted

At age 29 in 1919, Fisher took a temporary job at a small agricultural research station at Rothamsted. The director quickly saw that Fisher was a genius, and created a permanent post for him.

3.2 Weighing the Baby

Although he made astounding theoretical discoveries, Fisher had great interest in practical matters. In the textbook he wrote, Fisher used data he acquired by carefully weighing his own children to motivate a discussion of how best to plot data.

3.3 Find the Lady

In discussing the design of experiments, he uses another real-world example: At a scientific gathering, a lady declares that tea tastes different depending on whether the milk is poured into hot tea, or whether hot tea is poured into milk. On the spot, Fisher designs and executes an experiment to determine whether she can really taste the difference. It is said that this is a true story, and that the lady got nearly every test right.

3.4 From Soil Bacteria to Nonlinear Design

Many scientists visited Fisher for tea, and he became involved in their varied scientific pursuits, “often with dramatic consequences.” One such incidence of interest in another scientist's work lead to Fisher's pioneering work in nonlinear design.

3.5 From Cotton to Extreme Values

Another visitor to Rothamsted was concerned with cotton strength, which is limited by its weakest link. Work on this problem lead to a theory which has many different applications, and is considered its own field of study.

The rest of this section deals with work that Fisher did at Rothamsted and published in five volumes called “Studies in Crop Variation.”

3.6 From Dung to Orthogonal Polynomials and Residual Analysis

In “Studies in Crop Variation I” Fisher discusses the effect of different kinds of manure on crop yields. “In particular, he concludes that there is really nothing like plain dung.” Next, Fisher goes into the mathematical background which lead to his conclusions, wherein he introduces orthogonal polynomials and what we know call the analysis of variance or ANOVA. Box points out his discussion of residuals y-y(hat) as most interesting of all.

Box summarizes:

In the inferential stage, the analyst acts as a sponsor for the model. Conditional on the assumption of its truth he selects the best statistical procedures for analysis of the data. Having completed the analysis, however, he must switch his role from sponsor to critic.3 Conditional now on the contrary assumption that the model may be seriously faulty in one or more suspected or unsuspected ways he applies appropriate diagnostic checks, involving various kinds of residual analysis. (794)

Fisher then demonstrates mathematically that in order to maintain a small variance, one should use polynomials of smaller degree, an example of the value of parsimony. He also notes that extreme terms of the polynomial are greatly affected, which he calls “a weakness of the polynomial form” (794).

3.7 Weeds and the Education Acts

In the period of 1870--1880, wheat yields in all 13 fields were low, and not because of weather. These fields were weeded by young boys from a nearby school. Fisher implies an explanation of this low yield: "The Education Acts of 1876 and 1880 made attendance at school compulsory," (794) thus leaving the 13 fields choked with weeds and reducing yields. Note, however, that this wouldn't explain the low yields in the years prior to the first Education Act of 1876.

3.8 From Rainfall and Wheat Yield to Distributed Lags

In attempting to quantify the effect of rainfall on the 13 Broadbalk plots, Fisher was faced with too many regression factors (sunshine, soil nitrates, manure, weeding, etc) to produce a meaningful result. To get around this, he undertook a series of heavy calculations which we now call "distributed lag." Box points out Fisher's love of "parsimony" and notes that it may have been necessitated by Fisher's doing all this work by hand.

3.9 From Fertilizer and Potatoes to the Analysis of Variance

Fisher asks in “Studies in Crop Variation” whether there is an interaction between plant variety and fertilizer? Fisher does an analysis of variance (ANOVA). This may be Fisher's introduction of ANOVA. Fisher does the analysis of the plots incorrectly, but it gets corrected in the first edition of Statistical Methods.

3.10 Mice, Tigers, and Randomization

There's no mention of mice or tigers here, but it probably has to do with the earlier quote along the lines of “why bother with mice when there tigers about?” Box discusses (Fisher's?) table of a t-tests and Mann-Whitney tests on the same set of two samples of n=10 from a population of 1,000. The t-test is based on distributions and parameters, and the Mann-Whitney test is non-parametric. The point:

As is to be expected the significance level of the t-test is affected remarkably little by the drastic changes made in the marginal parent distribution-changes for which the distribution-free test provides insurance. Unfortunately, of course, both tests are equally impaired by error dependence unless randomization is introduced when they do about equally well. The point is, of course, that it is the act of randomization that is of major importance here not the introduction of the distribution-free test function.

The mice and tigers title suggests that one should worry about randomization (the tiger), not the type of test (the mouse).

3.11 From Muck Racking to Group Theory

Fisher had to apply special techniques to deal with a badly designed crop experiment. His friend William Gosset (of Student's t-test) suggested that he give them a hand in designing the next experiment, which Fisher did. Box uses this to illustrate the process of gathering existing data and using to create a preliminary experiment, then using data from that experiment to design a more statistically significant experiment to be carried out. This points out the shifting role of the statistician into a designer of experiments.

3.12 Evolution of the New Methods

Fisher came up with at least three tenets of good experimental design: “The need for randomization to achieve validity; for replication to provide a valid estimate of error; for blocking extraneous sources of disturbance to achieve accuracy.” This small section goes on to discuss something about blocking and Latin square. Box concludes:

However, while the efficiency of factorial designs could be increased by packing in more factors, larger factorial designs required bigger blocks and hence produced greater in-homogeneity in the experimental material, giving larger experimental errors. The answer which quickly followed was confounding.

3.13 Persuading Practitioners

By 1924, Fisher had finally convinced those at Rothamsted to implement his ideas about how to improve experiment design. By 1929, “data were being collected from designs of great accuracy and beauty which included all of Fisher's ideas.” However, in 1926 the director of Rothamsted, Sir John Russell, published a paper about agricultural experimentation which ignored nearly all of Fisher's ideas about experiment design. Fisher responded by publishing a paper in the next issue of the same journal outlining his own ideas.

3.14 A New Heritage for Statisticians

Rothamsted hired Fisher to see if anything more could be learned from years of existing data. But Fisher redesigned his role to begin not after experiments were run, but before they were designed. The statistician's “responsibility to the scientific team was that of the architect with the crucial job of ensuring that the investigational structure of a brand new experiment was sound and economical” (797).

4 Perils of the Open Loop

Extraordinary progress can be made when theory turns to practice, and practice returns to theory. One must not remain for too long in either the realm of theory or the realm of practice.

4.1 Cookbookery and Mathematistry

“Cookbookery” is to fall into using routines, or recipies, by rote, without giving too much thought to their implementation or interpretation or analysis. The other end of the spectrum is “mathematistry,” when a mathematician takes practical ideas to too far into theory, losing practical relevance and scientific usefulness.

Fisher was highly critical of mathematistry. Mathematistry may be harmless, except that it wastes the talents of those who might otherwise contribute to actual scientific progress. Or it may be harmful: Those who do not understand statistics may be overawed by mathematistry and may take its concepts too seriously, to the detriment of their experiments. A final danger of mathematistry is that too many statisticians will aspire to teach instead of practice. There should not be successive generations of statisticians without practical knowledge.

4.2 Meeting the Challenge

There will be an increasing need for competent statisticians.

4.3 Training of Statisticians

A proper balance of theory and practice is needed and, most important, statisticians must learn how to be good scientists; a talent which has to be acquired by experience and example.

Fisher warns sternly against directing the most talented statisticians towards theory and away from practice.

5 Conclusion

Box concludes:

We may ask of Fisher: Was he an applied statistician? Was he a mathematical statistician? Was he a data analyst? Was he a designer of investigations?

It is surely because he was all of these that he was much more than the sum of the parts. He provides an example we can seek to follow.

Thanks, George.

Photo source: DavidMCEddy at en.wikipedia [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or

CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Photo source: DavidMCEddy at en.wikipedia [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or

CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons